Click here to

see this email on the web

|

|

Thursday, November 2nd, 2023

|

|

The #1 Thing You Need to Paint Better Trees

|

By Christopher Volpe

|

Share this article:

|

|

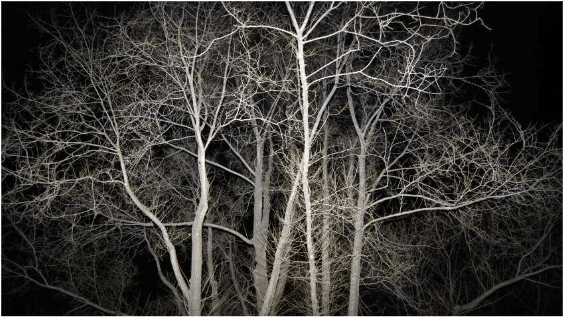

Albert Handell, Mother Tree, pastel, 16” x 20”

|

The Number One Thing you need to paint better trees is to understand trees better. That’s the surprising verdict of 20th century landscapist and author John Carlson. Carlson literally wrote the book on landscape painting that no landscape artist should be without.

In the classic Carlson’s Guide to Landscape Painting, he says, “It is curious how one’s feelings about trees change in proportion to one’s appreciation of their importance and dignity as live beings. Trees are individual beings: they can be comic, heroic, tragic to the sensitive, practiced eye of the landscape artist.”

See, the thing about Carlson is that he doesn’t tell you how to paint the trees, he tells you how to know the trees – and THAT makes all the difference in how you paint them. Carlson’s chapter on trees is titled not “how to paint trees” but “Trees: How to Understand Them.” This man was the Doctor Doolittle of the oaks, maples and pines.

|

|

John F. Carlson, Woods in Winter, ca. 1912, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift from the Trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art

|

“Know your trees,” Carlson urges the artist, “their nature, their growth, their movement; understand that they are conscious, living things, with tribulations and desires not wholly disassociated from your own.”

It sounds like whimsical woo-woo but, Carlson’s essay really will teach you how to make the best trees you’ve ever done. Consider the following next time you’re about to paint a forest interior or any group of trees standing together:

“A tree seldom or never encroaches upon the liberty of another tree, if it can be avoided. Usually ‘both parties’ settle equitably, and without ‘due process.’ A tree recognizes that its liberty ends where the next tree’s liberty begins.”

“A tree never wastes its growth in unnecessary twistings, nor in frivolous waste of energy,” Carlson observes. “If a tree is seen to twist and turn (within its type’s specific scope), these turns and twists are intimately connected with, or in rapport with, the turnings and twistings of a neighboring tree. This engenders a certain rhythm or flow of related lines in a wood.”

|

— advertisement —

|

|

|

Albert Handell, L’Arbre ‐ Oil ‐ 18 x 31

|

Trees – How to Understand Them is filled with similar passages of delightful prose and rare insights that will inform your tree painting.

Carlson ensures that to the sensitive reader, a stand of trees will never be just what he terms, “a heterogeneous multitude of vertical sticks.”

Such are the unlooked-for rewards of becoming an artist: the small gifts that enrich daily life. As to the ultimate insight, Carlson offers the following hint:

“The specific life-germ that established the differing species in differing climes is as mysterious today as ever. We have, as Carlyle says, proceeded but a hand’s-breadth into the mysteries of nature.”

|

|

Paul Kratter Under the Sycamores, 12×20 inches, oil on panel. Kratter shares his own processes and insights for masterful tree painting on video.

|

Browse a wealth of titles on trees and other landscape painting essentials by Albert Handell, Paul Kratter, and many others here.

|

|

|

|

— advertisement —

|

|

|

iStockphoto.com

|

The Logic of Branching Out: A Brief Guide to Believable Trees

|

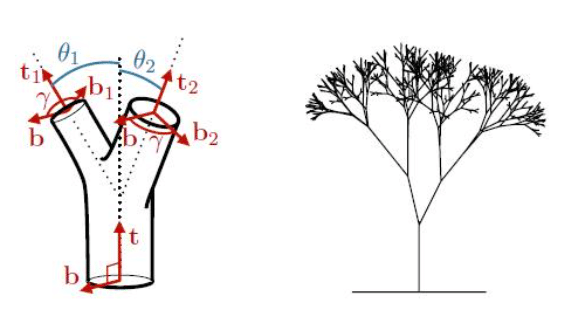

Leonardo DaVinci observed (and later scientists confirmed) that when trees branch, smaller branches have a precise mathematical relationship to the branch they sprang from.

Simplified for the landscapist, the general rule to follow is: Anytime a tree limb splits, the smaller branches “add up to” the original branch. Makes sense: if anything breaks up, its parts never exceed the whole.

Da Vinci was thinking in terms of the tree as a whole. He wrote in his notebook that, “all the branches of a tree at every stage of its height when put together are equal in thickness to the trunk.” In other words, if a tree’s branches were folded upward and squeezed together, the tree would look like one big trunk with the same thickness from top to bottom.

|

|

Diagram and mathematical illustration accompanying Christophe Eloy’s paper, “Leonardo’s Rule, Self-Similarity, and Wind-Induced Stresses in Trees” published in Physical Review.

|

In 2011 a French physicist discovered the reason for this principle of tree branching. Christophe Eloy was on a break from his day job as an assistant professor at the University of Provence when he discovered that Leonardo’s rule “is a consequence of … branch diameters being adjusted to resist wind-induced loads.” In other words, from an engineering point of view, if you wanted to design a tree that was best able to withstand high winds, applying Leonardo’s rule is exactly how you’d do it.

Keeping Leonard’s rule in mind when painting trees goes a long way toward making them more believable to viewers.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inside Art is committed to protecting and respecting your privacy. We do not rent or share your email address. By submitting your email address, you consent to Streamline Publishing delivering regular email issues and advertisements. To end your Inside Art e-mail subscription and associated external offers, unsubscribe here. To learn more about Streamline Publishing events, products, and offerings visit StreamlinePublishing.com

Copyright 2022 Streamline Publishing, Inc. All rights reserved.

Inside Art® is a registered trademark of Streamline Publishing, Inc. |

|

|

|

|